Solving Cache Line Contention in Large NUMA Systems

Introduction

EnterpriseDB® (EDB™) works with a significant number of global brands that deploy EDB Postgres to support complex business-critical workloads. Some of these brands experienced a dramatic drop-offs in performance as they dialed-up the concurrency in their load tests. This was a mystery for these brands, and we wanted to help them solve it.

A clue to this mystery: Prior to using new hardware, tests could handle upwards of 500 concurrent sessions with EDB Postgres. However, once these brands began using their shiny new hardware, they couldn’t get past 300 users (and one couldn’t get past 140) without grinding to a halt.

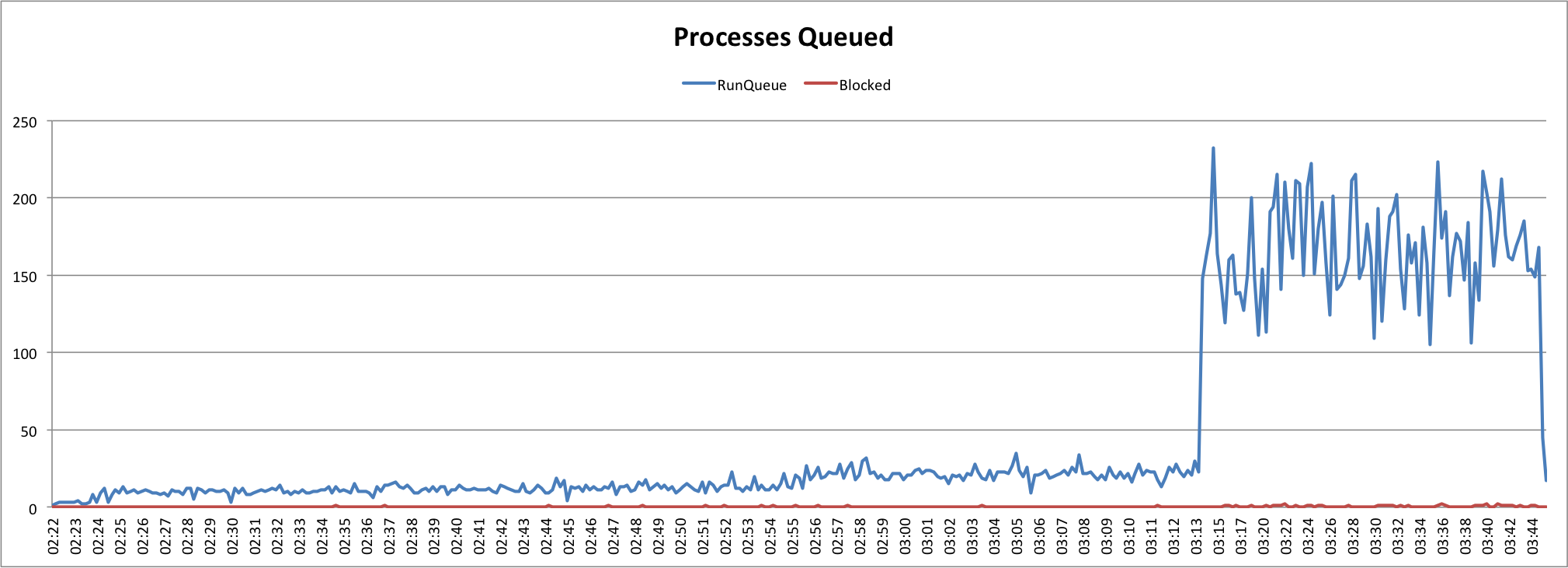

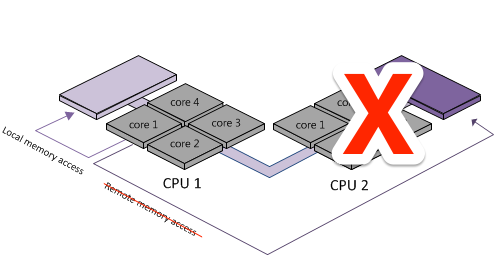

We began our investigation and ultimately determined the cause for these lock-ups was due to a phenomenon that can be described as “Cache Line Contention in Large NUMA Systems.” That’s a mouthful, so we’ve shortened it to “NUMA vs. spinlock contention.” Simply put, when processes want to access particular memory segments, they use spinlocks (don’t go looking in pg_locks for this!), and wait for the OS scheduler to give them access to memory (and potentially move it between NUMA nodes). Without getting into all the minute details, we found that NUMA vs. spinlock contention typically occurs on OLTP workloads that use enough memory to span multiple NUMA memory segments, but where the most active set of data is confined to one memory segment. What it amounts to is a lot of waiting around, moving data between memory regions, and the appearance of the CPU doing a lot of work.

If you’d like to know more about NUMA, and NUMA vs. spinlock contention, you can check out the following resources. (Note: SQL Server also experiences this phenomenon):

- NUMA

- Cache Line Contention

Thankfully, newer Linux kernels (v. 3.8 and later, which translates to RHEL/CentOS 7 and Ubuntu 13.04) have improved NUMA policies, which mitigates the effects of this contention. With one particular customer, the upgrade from RHEL 6 to RHEL 7 made the problem disappear without any additional tweaking.

Is this for me?

Now, you may ask, “I’m having trouble scaling, could this be NUMA vs. spinlock contention?” Maybe. Maybe not.

You’ll want to consider these factors before proceeding:

- Are you using new hardware? And does the new hardware not perform as well as the old hardware?

- Are you running an OLTP load against the database?

- Do you see performance degrade suddenly with the addition of another user/process? Are you sure performance is not degrading gradually?

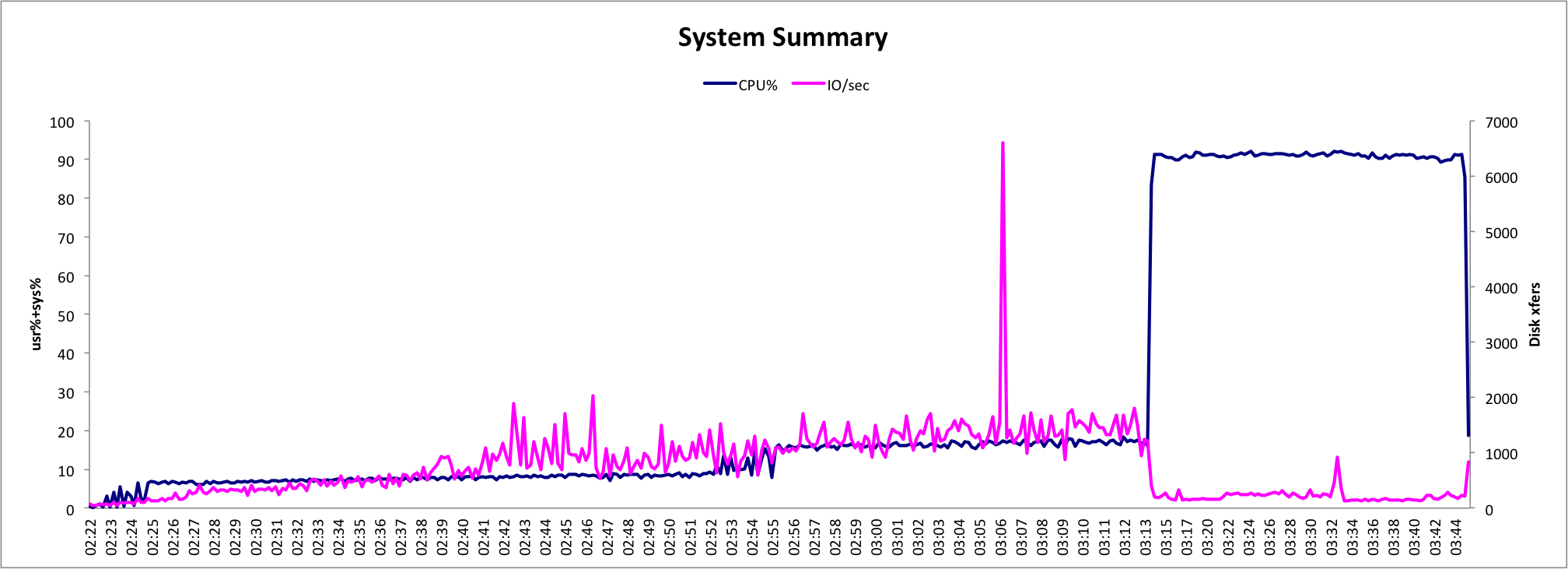

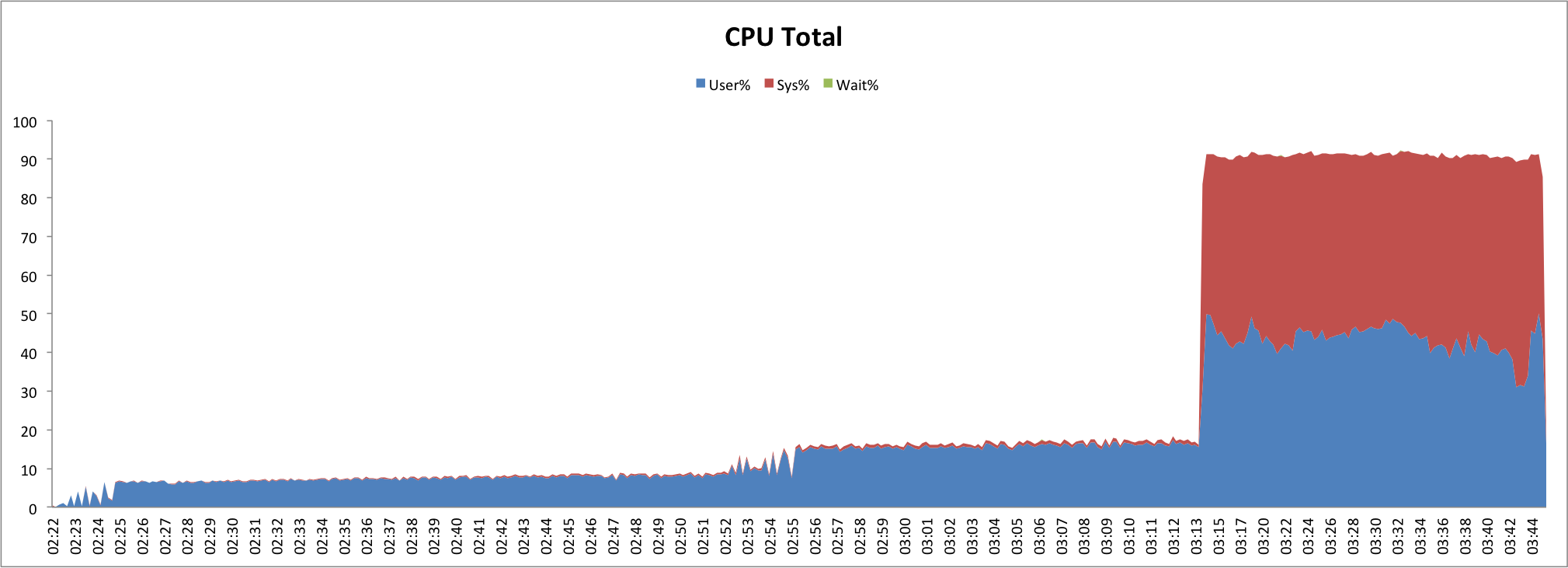

- Do you see high CPU utilization, especially in %sys?

If you can answer “yes” to all of these questions, there’s a good chance your NUMA nodes are suffering from cache line contention, and you might want to read on. If not, you may or may not be experiencing this phenomenon, but please feel free to read on anyway.

An example of what you might see in CPU activity would be something like the following:

Identifying the Culprit

The way to tell definitively if your NUMA nodes are causing headaches is to simply remove NUMA handling from your server. If you limit your processing to one CPU socket, you won’t be passing data between memory regions, and therefore you won’t experience cache line contention. How can you do this? By creating a cpuset and running your Postgres server on that one cpuset. That way, you’re running on one NUMA node, and all your data is confined to one memory region. If you do this, and you see your performance reach desired/previous values, you can be certain that cache line contention is causing the performance hit – and it’s time to upgrade the OS or look for other ways to get around the NUMA v. spinlocks issue.

The Plan

Setting up a cpuset

The process by which you set-up a single cpuset on a Linux system varies by distribution. The following steps work for the general case, and applies to both Community PostgreSQL and Postgres Plus Advanced Server:

# to see where the cpuset "home" directory is:

mount | grep cpuset

# to see the OS user and parameters for starting the server:

ps -ef | grep postgres

# to see what the cores are and what memory is attached to each

numactl --hardware

# fill in with a hyphenated range based on output of “node 0 cpus” of `numactl --hardware`

# EXAMPLE: NUMA0_CPUS=”0-14,60-74”

NUMA0_CPUS=””

# to make things easier to consistently reference, something similar to:

export CPUSET_HOME="<path where cpusets are mounted>"

export PGSERVERUSER=<whatever OS user runs the service>

# set up the single-package cpuset

sudo mkdir $CPUSET_HOME/postgres

sudo /bin/bash -c "echo $NUMA0_CPUS >$CPUSET_HOME/postgres/cpus"

sudo /bin/bash -c "echo '0' >$CPUSET_HOME/postgres/mems"

sudo chown $PGSERVERUSER $CPUSET_HOME/postgres/tasks

# start the database service on the special cpuset for testing

sudo su - $PGSERVERUSER

export CPUSET_HOME="<path where cpusets are mounted>"

echo $$ >$CPUSET_HOME/postgres/tasks

pg_ctl start <usual start parameters>NOTE: do not use sysctl or service or /etc/init.d/ scripts to start Postgres–be sure to just use plain old pg_ctl to ensure that the server gets started on the cpuset you created.

If this doesn’t work for you, you’ll need to do a bit of Googling around for cpusets, or to find a way to limit all your Postgres processes to one CPU.

Once you’ve set up the cpuset and verified Postgres is running, and you can log in, start-up your application(s) and/or tests and see if performance improves. Watch the CPU graph to make sure that only a fraction of your processors are actually being utilized. If you are able to achieve better performance, you can be quite certain that NUMA cache line contention is the cause for your earlier performance degradation.

The Mystery Solved

From here, you will want to ensure that your Linux kernel is up-to-date with the latest kernel-level NUMA-handling features. If upgrading your OS is not an option, you may want to look into other ways around the issue, such as:

- Create a separate cpuset for each Postgres cluster/instance;

- Limit your real database connections to a safe level with a connection pooler (like pgbouncer);

- Consider other hardware;

- Spread your data and workload across different servers.

Note: This was originally posted on the EnterpriseDB blog